by Jely A. Galang, Ph.D.

Chinese Workers and “Criminals”

18 June 2021 – At midnight, on June 19, 1877, some members of the Guardia Civil Veterana (city police) found Lim Oco sleeping in front of a closed shop in Sta. Cruz, Manila. When asked for his cedula (tax registration certificate), this drunk Chinese could not produce one and even attempted to run away, except that he was immediately seized by the arresting officers. He was charged with vagrancy, drunkenness, sleeping in an unauthorized premise and for being undocumented. Upon his admission to the Bilibid Prison, it was found that this former stevedore had already been arrested three times for the same offenses. Yet on each occasion, he was released from prison and returned to his “life of idleness and uselessness.”[1] After serving three months as a convict laborer, the state banished him and other “criminals” to Jolo to build military fortifications.[2]

Lim Oco’s story is not an isolated case. Based on my research on the laboring class Chinese in the nineteenth century Philippines, thousands of ordinary Chinese were arrested for violating certain crimes. They were considered “dangerous” by the colonial government because they posed a threat to the colony’s financial and political security. Like Lim Oco, most of them belonged to the working-class and were classified under the lowest tax category. They claimed that the nature of their work¾temporary, back-breaking and low-paying¾made it impossible for them to satisfy their tax obligations. Also, due to their precarious working conditions, they had the propensity to commit “crimes” like vagrancy, insolvency, larceny, not possessing identification papers, idleness and drunkenness.

The lives of these Chinese workers and those who became “criminals” are worth examining but not much is written about them. Unlike the merchants who have been the focus of studies,[3] these individuals are still invisible in the historical narrative. This historiographical lacuna stems from the scarcity of documents needed to reconstruct their collective biography. Whereas Chinese merchants left materials about their lives and business activities, ordinary Chinese left no records about themselves. They only appear in archival materials when they came into conflict with the authorities. Their personal data, and living and employment arrangements are found in police dossiers, prison records, court proceedings and arrest orders. In these records, they insisted that they were not criminals; for them, the offenses they did were actually a necessary means to survive. Hence, I put “crimes” and “criminals” in quotation marks to highlight the need to problematize these juridical terms.[4]

Criminal Records in the Archives

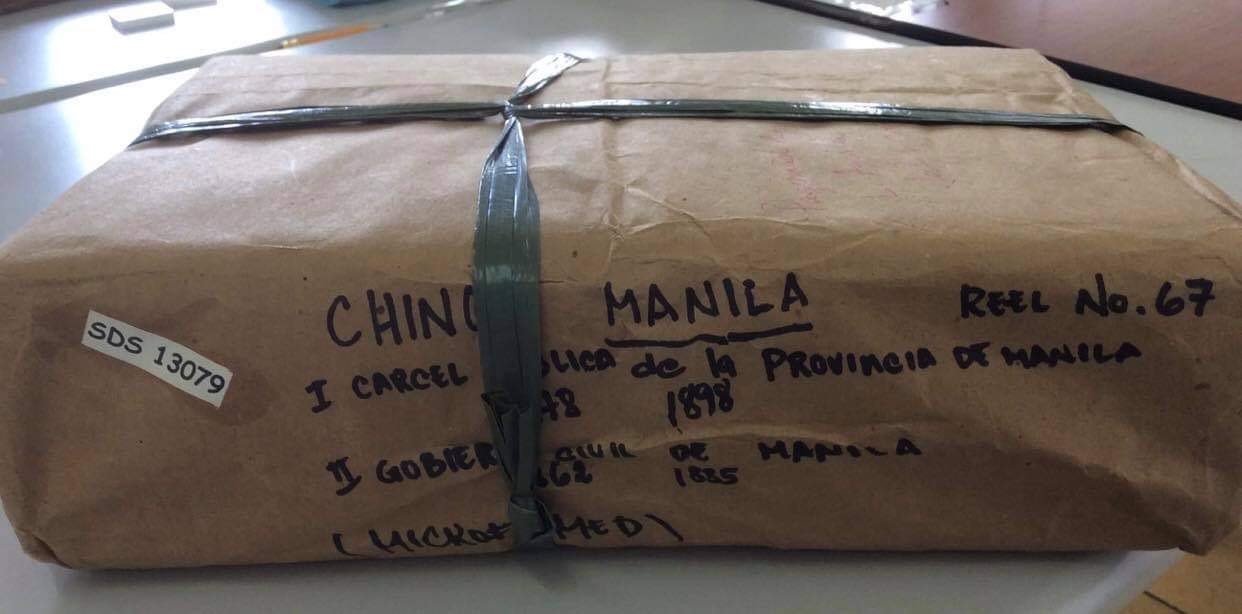

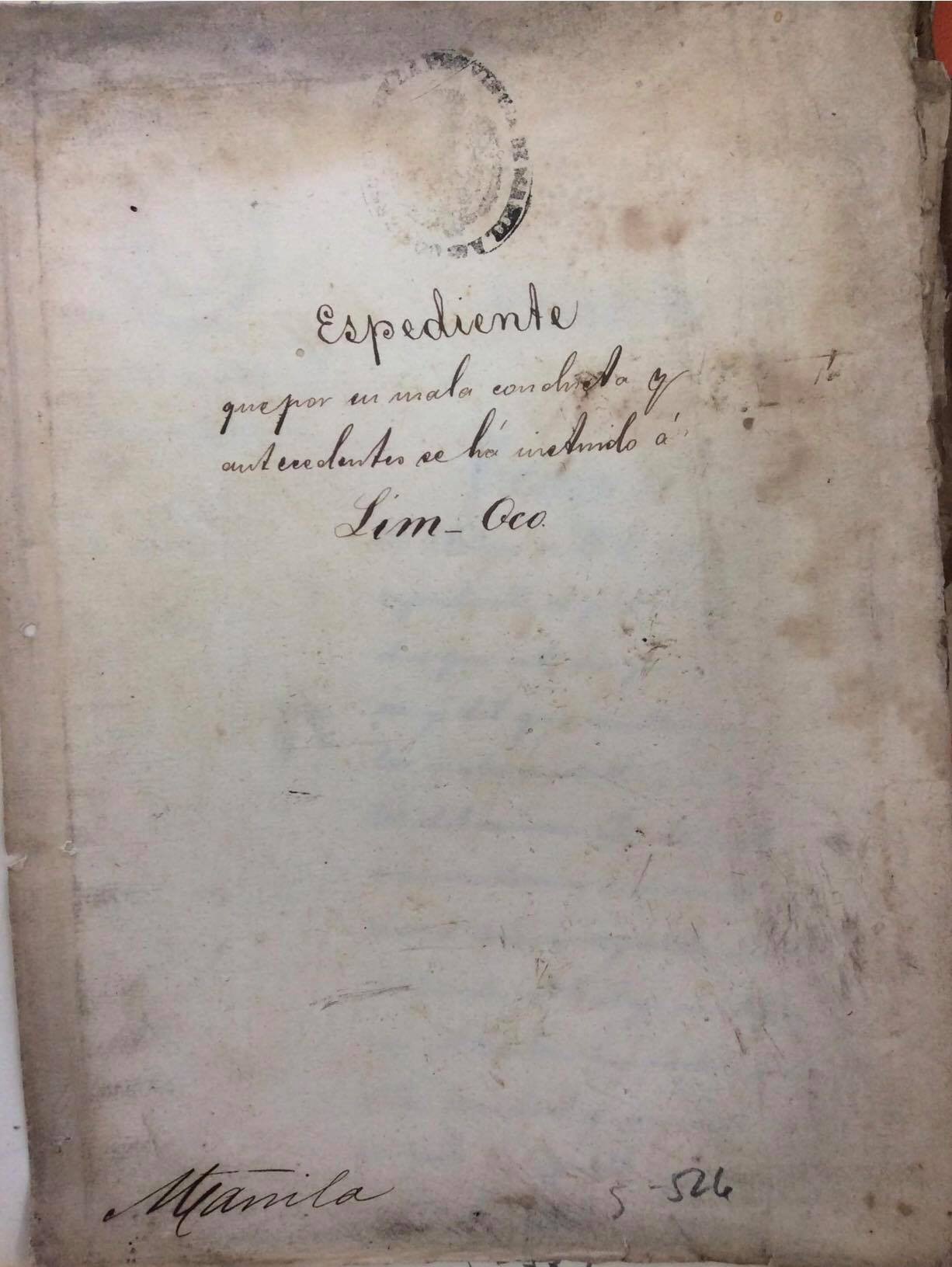

The criminal records I used for my research mostly came from different repositories like the National Archives of the Philippines (NAP) in Manila and the Archivo Historico Nacionál (AHN) in Madrid. The key sources of data I used at the NAP were the 148 Chinos bundles, which contained documents on the Chinese in the Philippines from the 1780s to 1900. These bundles were categorized per province: 103 from Manila, 39 from various provinces, and the remaining six “Miscellaneous Documents” bundles were materials with unspecified provenance. In particular, I reconstructed Lim Oco’s case using two Chinos bundles: SDS 13079 contained materials related to his arrest and preliminary investigations while SDS 13082 covered the court proceedings in Binondo and his incarceration in Bilibid Prison.

NAP, Chinos (Manila, 1878-1787), SDS 13079. Courtesy of the National Archives of the Philippines (taken by the author, Feb. 10, 2016)

Expediente (File) about Lim Oco NAP, Chinos (Manila, 1878-1787), SDS 13079, S 526. Courtesy of the National Archives of the Philippines (taken by the author, Feb. 10, 2016)

Materials at the AHN related to the Chinese in the Philippines, on the other hand, are in the “Ultramar” (Overseas) bundles. These materials pertained to various policies imposed upon the Chinese. There were correspondences and administrative inquiries between Philippine Governors-General and Madrid officials regarding issues like the imposition of the cedula and the commutation of the corvée labor, Chinese immigration and economic activities in Mindanao, and deportation of “criminals” to different areas of the archipelago. There were also letters on various political and socio-economic reforms aimed at controlling the Chinese, and on how the state could benefit from them more effectively. It was from the bundle Ultramar 5230 that I found the final part of Lim Oco’s interesting story—his banishment from Manila to Jolo.

The author in front of the Archivo Historico Nacionál (Madrid) (photo taken by the author, July 2019)

A Researcher in the Archives

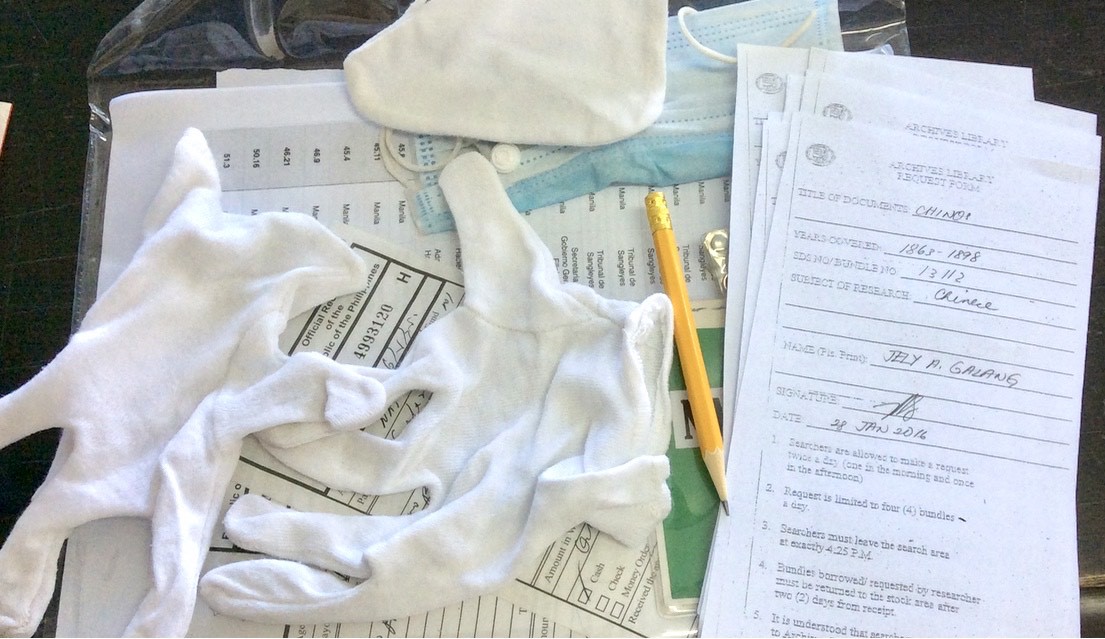

Doing research in the archives is quite challenging. It took me some time before I was able to fully come to grips and tame the voluminous materials relevant to my topic. At the NAP, it was an overwhelming experience to know, for instance, that there were more than a hundred Chinos bundles, and hundreds of related bundles—such as asuntos criminales (criminal matters), carceles (jails), presidios (military fortresses), and presos (prisoners) among many others—that I could consult. And given my limited time for research (about four months) and the limited number of bundles I was allowed to open (four bundles per day), I had to find the best way I could efficiently use my time.

Also, apart from the challenge in opening and handling dusty, brittle and, in some cases, disintegrating manuscripts, another concern was the difficulty in reading some documents because of the cursive handwriting was terribly hard to decipher. There were documents in NAP, Chinos Manila, SDS 13063, for example, that provided information on house inspections in Manila in the 1880s with the purpose of capturing undocumented and insolvent Chinese workers. While the police reports were clearly written and understandable, the records on how the arrested individuals were tried and punished were not written legibly. The way these records were penned gives the impression that the court clerk was too lazy or too bored to write down the proceedings properly.

When I did my research at the NAP in 2015-2016, researchers could copy the documents by hand or by using laptops. We were also allowed, after securing permission, to take photos of pertinent materials. Each shot cost a certain amount. I wrote down the summaries of important files and took photos of the relevant pages so I could read them again in my office. Researchers at the AHN, on the other hand, are not allowed to take photos of the documents. They can either request the staff to scan the documents (also for a fee) or they themselves can copy the documents by hand. When I was there in 2016 and 2019, I copied the texts as they appeared on the documents. Historian Arlette Farge claims that “[a]n archival document recopied by hand onto a blank page is a fragment of a past time…”[5] For her, this aspect of research is “time-consuming, [and physically exhausting as] it cramps your shoulder, and stiffens your neck. But it is through this action that meaning is discovered.”[6]

A researcher’s “essentials”: cloth hand gloves, face mask, handkerchief, pencil, note pad, transparent envelope, list of materials to consult, NAP researcher’s ID, NAP request forms (photo taken by the author at the NAP Reading Room, Jan. 28, 2016)

Despite these challenges, archival work is also exciting as one does not know what is to be discovered. A curious researcher would open a bundle and serendipitously unearth an information that would lead to a new, interesting research. At the AHN, when I was looking for materials on Lim Oco, I located a file about a German-owned tobacco company in Jolo that employed Chinese laborers. I did more research about this unknown plantation and later wrote an article about it.[7] Moreover, there is the excitement in being able to enter the world of the documents and, in these materials, locate the voices of the ordinary Chinese. Although I was working with criminal records framed around legal definitions, I gleaned a lot of things from them about the lives, feelings and struggles of the poor Chinese. The story I was attempting to reconstruct could now be told from the standpoint of the authorities and from the “criminals” themselves.

Archival research is also rewarding when one is able to finally put the bits and pieces of his data together and come up with a coherent narrative. From the Chinos bundles, I gathered more than 5,000 criminal cases from 1831 to the end of the Spanish regime in 1898. I assembled the details from these cases in order to describe and analyze the Dickensian living and working conditions of laboring class Chinese, the socio-economic challenges they confronted as well as the overt and covert ways they evaded the authorities in order to survive. I found out that to understand their lives and circumstances, one has to examine them within the broader milieus of the period and interrogate the actors, institutions and processes involved in their transformation from being ordinary laborers to “criminals.”

An Invitation

Chinese laborers were an important part of the social and economic life of the Philippines during the nineteenth century but, as noted, studies about them are extremely limited. Fortunately, various archives house primary documents—mainly criminal records—on which to base a reconstruction of their stories. These documents, although written from the point of view of the state, provide information about these lower-class Chinese. These materials, however, must be critically evaluated before they can be utilized.

Lim Oco’s story is only one of the many stories of ordinary Chinese that I discovered in the archives. Their stories demonstrate another facet of the Chinese community in colonial Philippines, a community that has been commonly portrayed as a homogenous and affluent group. Their stories also serve as an invitation to (re)examine how vast population of “social outcasts”—vagrants, beggars, unemployed, idlers and the homeless—in the past (as well as in the contemporary period) were “created,” defined, criminalized and punished because of their social condition of unemployment, material deprivation and sinking status.

This piece is based on his research for his doctoral dissertation “Vagrants and Outcasts: Chinese Laboring Classes, Criminality and the State in the Philippines, 1831-1898” (Murdoch University, 2019). Here is the link to his dissertation: https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/45556/

[1] NAP, Chinos (Manila, 1878-1898), SDS 13079, S 527-532.

[2] NAP, Chinos (Manila, 1890-1898), SDS 13082, S 260b; AHN, Ultramar 5230, Expediente 40, No. 5, Letter of Domingo Moriones (Manila, October 18, 1877).

[3] see Richard Chu, Chinese and Chinese Mestizos of Manila: Family, Identity, and Culture, 1860s-1930s (Mandaluyong City: Anvil Publishing, Inc., 2012); Andrew Wilson. Ambition and Identity: China and the Chinese in the Colonial Philippines (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004).

[4] Patricia O’Brien, “Crime and Punishment as Historical Problem,” Journal of Social History, 2: 4 (1978), 508-520.

[5] Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2013), 17.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jely A. Galang, “Hacienda Gomantong: The 1888 Chinese Immigration Decree, A German Tobacco Plantation and Chinese Laborers in Jolo, Sulu, Southern Philippines,” Asian Studies, 56: 2 (2020), pp. 1-32.